|

What is proactive policing?

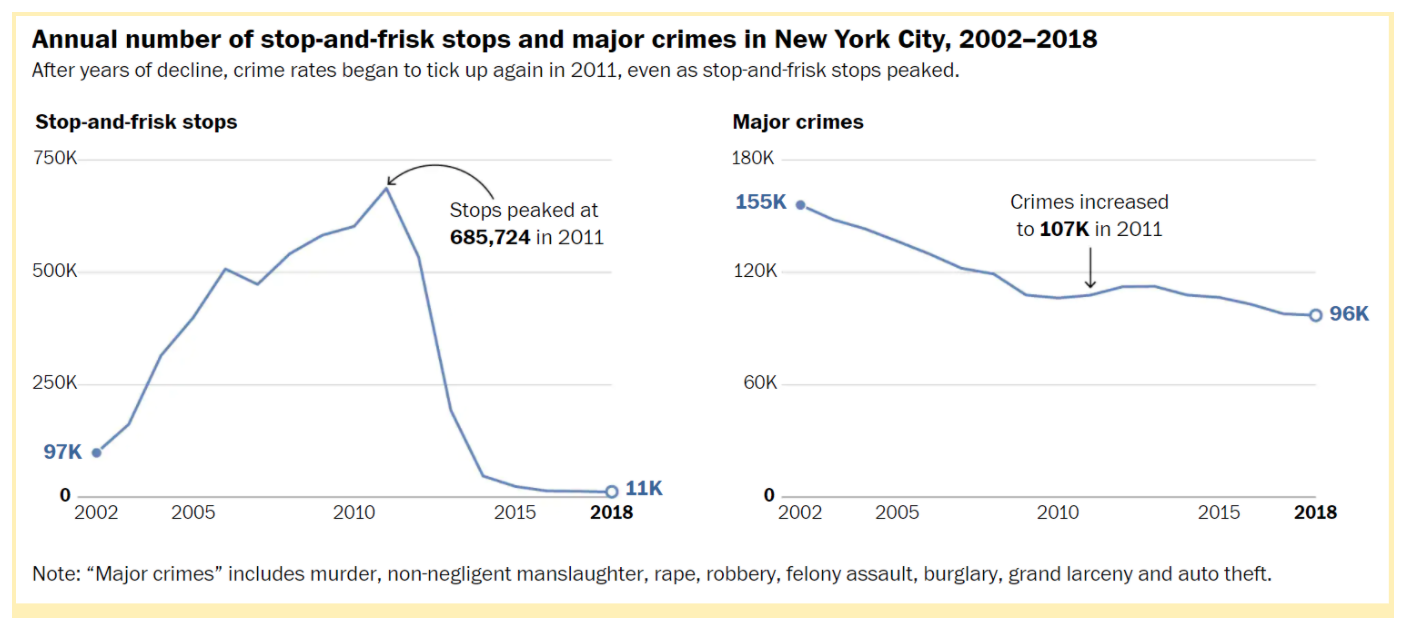

While reactive and traditional policing is the act of responding to a crime after it’s been committed, proactive policing is a method of seeking out and deterring crime before it occurs through police presence and show of force. A commonly cited example of proactive policing is “stop-and-frisk”, which is the practice of detaining, questioning and/or searching any civilian on the street for weapons or other contraband. Proactive policing is also the practice of increasing police presence in certain areas to send a message to the public - we are here and we are watching you. Proactive policing relies on the assumption of potential guilt, which is contrary to one of our most basic democratic principles of justice -- that citizens are innocent until proven guilty. Does it work? It’s hard to say. It might, but not without significant consequences. A recent opinion piece on CNN from an American law enforcement analyst and retired FBI agent who mostly worked in New York City stated that “studies [on proactive policing] have provided evidence they can prevent or reduce crime.” Yet, an analysis by the Washington Post found that, while major felonies declined in New York City from 2002 through 2013 (when stop-and-frisk was implemented by the mayor), the reduction did not correspond to the increase in stops by police. According to Washington Post, “crime has continued to fall since a federal judge deemed the practice an unconstitutional violation of civil rights in 2013.” An analysis by the New York City Civil Liberties Union showed that, at the height of stop-and-frisk in NYC in 2011, over 685,000 citizens were stopped. Nearly 9 out of 10 stopped-and-frisked New Yorkers have been completely innocent. And racialized people continue to be the overwhelming target of this practice. What are the consequences in the Calgary context? A proactive policing approach in Calgary would see an increase in patrols in high-crime areas like downtown and the northeast -- where there is a high percentage of racialized and/or marginalized people, many of whom are criminalised and excluded from participation in high paying jobs. This will inevitably lead to an increase in racial profiling of innocent civilians, and erode any sense of trust and community belonging amongst those civilians. Increased police presence and force sends a clear message to these communities, and especially impressionable youth, that there is something wrong with them and they do not belong here. When people feel ostracized from the community, or that they don’t belong there, they lose any sense of responsibility to that community, including keeping it safe. Why would anyone be concerned with a community that is actively telling them they are unwelcome and under suspicion? This will also add to the already highly disproportionate numbers of Indigenous and Black people in correctional facilities. The initial instance of incarceration often leads to cyclical involvement in the justice system and extreme social inequality. Regardless of the work one has done to make up for a past crime, that criminal record will be a constant barrier to employment, housing, education and other necessities to lift oneself out of this cycle. Ongoing probation continues to send a message to criminalized people: we do not trust you. Add on increased police presence to this cycle and the message is clear: you are not to be trusted. So, why would people are told they are criminals trust the very people who keep telling them they are criminal? Why does crime happen in the first place? Trauma and poverty are inextricably linked. Trauma, especially during childhood, changes the way one’s brain is wired. According to brain science, without positive interventions, this causes the brain to continue exhibiting those fight-or-flight responses which greatly increases the likelihood of criminal behaviour as an individual ages. Poverty and unemployment are also strong indicators of incarceration rates. Racism and poverty are forms of trauma, as are negative interactions with law enforcement, especially when they are unwarranted. If increased policing results in increased trauma, it will inevitably lead to an increase in crime. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. What’s the alternative? We can effectively reduce and prevent crime without negative long-term consequences by addressing the root causes of crime such as poverty, unemployment, lack of belonging and trauma. It’s not only the more humane and just thing to do, it will actually lead to a more prosperous Calgary for all, and increased trust and engagement with police. A percentage of the police budget must be reallocated to social programs that address the root causes of crime through an anti-racist, trauma-informed lens, rather than continuing to increase funding to the never-ending cycle of the justice system and agencies that don’t actively address systemic and interpersonal racism on a daily and operational basis. This approach is proven to work: for example, Glasgow, Scotland's most populous city, lowered its murder rate by 50% through "smart law enforcement" combined with "programs targeted to youth, family health and other services in problem places." This may mean that the City of Calgary needs to look at new organizations, lead by people with lived experience of, and expertise in racism, for this movement to be effective. It will be a process, rather than an overnight phenomenon. But it is necessary for the health and wellbeing of all citizens in Calgary. We know that criminalizing people does not work in the long term and “proactive policing” sends a message that certain people and certain areas of the city are not to be trusted. Let’s move Calgary forward and use a modern approach to policing that builds respect and resilience into the community we all call home.

1 Comment

|

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed